An essay I wrote almost 5 years ago now about the role the media plays on how Africa is viewed. Still just as relevant now as it was then. I have had to convert it into wordpress form and as a result, the picture in it is very unclear, the references were also not added at the end of the essay. Enjoy!

New Orleans: a vibrant city, bursting to the seams with culture, the birthplace of jazz and legends like Louis Armstrong, and the gateway to the Mighty Mississippi River. No other city is quite like it, with its scintillating nightlife and burlesque shows, waterways that criss-cross the entire city, a mix of races and culture too numerous to quantify, all fused into one city. The temperature is just perfect. The most unique multicultural city in the US which has both sweeping plantation homes as old as the city on one part; and some slightly less grand city dwellings on the other. A democratic political system where people can aspire to be presidents and marvel at the distinct French-creole architectural style. The name alone conjures up new beginnings and a bucketful of hope….

I’ve never been there though. How is it that I can describe the architecture, history and social life as a native inhabitant might? How did I know about the Mardi gras celebrations and the French-creole architectures? The more I thought about it the more I realised, I hadn’t set out to broaden my horizons, and neither did I find out about New Orleans to be able to participate in a discussion about American carnivals. In fact I hadn’t actively sought out information about it. I hadn’t ‘googled’ it and sat through page after page of interlinking Wikipedia articles. It was simply there. A huge database of information consisting of random snippets from various films, documentaries and cartoons condensed into a general knowledge of the city. I didn’t know about the Mardi Gras until I watched the Disney film: “The Princess and the Frog”. (Twins, 2010) As a result I didn’t have to think to describe New Orleans, even though I’d never tasted the air or smelt the Mississippi’s unique scent.

Trying to visualise an African city however posed a different set of challenges. It wasn’t a lack of information or underexposure to stories from the continent. The crux of the problem was negativity. I had to consciously sift through the countries to find the most positive. Every time I tried to think of a city in Africa my mind immediately started playing back documentaries about desertification, famine, civil war, genocide, even the Hollywood film: “Black Hawk Down”. (Pathay, 2001). I realised that my subconscious was selecting the country I knew most about. My mind was stuck on Somalia. I was halfway into my brainstorming before I realised my level of ignorance on the small matter of cities within Somalia.

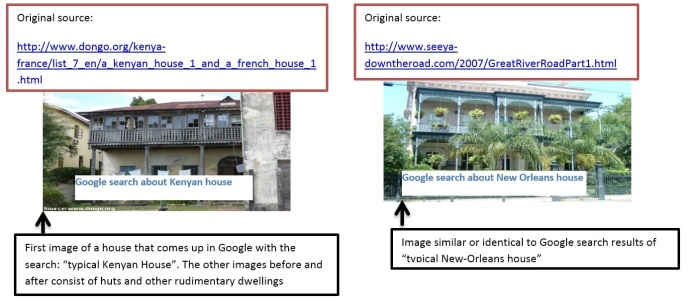

It occurred to me that while the media brought stories about the country they never described the country farther than on an international level. Apart from Mogadishu I had no idea of the other cities. I was guilty of failing one of the fundamental judging points I used for strangers. On my first day of secondary school in the UK a well-meaning girl came up to me and gently asked where I came from. To which I replied Nigeria. After elaborating further, she was able to get a grip on the location. Puzzled, she asked me how a country could exist within another country. This was when I realised that she had a view of Africa as a country not a continent. I can’t blame her for it though as we were both young and naïve. However a similar occurrence happened in year 10 when a girl asked me which type of hut I used to live in as she had seen some on holiday to Tanzania. This question I found much more difficult to understand. A quick Google search reveals why she asked:

The similar results section in Google asked me to specify my search result even farther to “Kenyan poor houses”. Whilst this was no fault of Google, it was simply displaying the most common search terms to do with Kenya. People do not generally expect much in the way of infrastructure from Africa, this stems from the images beamed to us through our news channels and television screens. Ultimately when they search for Kenyan houses on Google they specify the search to show what they perceive as a normal African house…or “poor house” My father once cried out in exasperation when a BBC correspondent was interviewed in the Nigerian capital of Abuja. He was moved to tears of frustration when the correspondent was interviewed in front of an open market in the rundown outskirts of the city. I was younger then and I did not realise his frustration. The BBC chose to show archive footage of a run-down area to support the correspondent’s report on the country’s politics. The city of Abuja is a mega-city custom built out of the lush savannah, a similar feat to the construction of Las-Vegas with stunning architectures and it is one of the most modernised in Africa. Whilst the BBC may have not acted deliberately, they inadvertently fed into the belief that Nigeria’s flagship city is nothing to write home about. It was then that I realised that our perceptions of the Third World, especially Africa are mostly shaped by what we see, hear and read in the media. The media does not deliberately go out of its way to portray Africa in a bad light; it reports on the latest famine in Somalia, the latest genocide in Rwanda and atrocities in Libya because it wants to inspire, it wants people to act and donate or buy fair-trade because it cares to make a difference. The problem however is that too much of the same kind of story is not good for a place. Just as my description of New-Orleans sounds too sweet and sickly, so does my description of Somalia sound too violent and harrowing. I don’t advocate that we simply bury our heads in the sand and pretend that people are not threading a fine line between life and death in Somalia. Neither am I suggesting that we go out of our way to portray Somalia as a Garden of Eden, like my idealised view on New-Orleans. In reality New-Orleans is still recovering from the destruction caused by hurricane Katrina, race equality is one of the worst in America and many ethnic minorities live in places similar to a Third World city.

“On September 22 the Census Bureau released information from their 2010 annual American Community Survey based on a poll of 2,500 people in New Orleans. Not surprisingly, the report was ignored by the local mainstream media since it speaks volumes about the inequality of the Katrina recovery. The survey revealed that 27% of New Orleans adults now live in poverty and 42% of children… The new spike in poverty signal that blacks are not sharing equally in the employment benefits of recovery dollars. Indeed, the city may be creating a new generation of chronically unemployed poor who were previously part of the low-wage working poor.” (Hill, 2011)

For a MEDC the figures above are unacceptable and it shows the gap between minorities. As stated The media largely ignored this as it portrayed the city in a bad light. Without doing any independent research of my own I would not have known that such levels of inequality exist in the United States. Yet I know that thousands of people have fled Somalia due to conflict and even more have died from famine and related causes. I know that as recently as a few weeks ago, hundreds of people died and thousands were displaced when a ‘tribe’ went to war with a neighbouring tribe over stolen cattle (ABC, 2012). I didn’t research it but the news media chose to broadcast it. The danger in press practices like this is that people fall into the trap of a ‘single story’. According to a prominent Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie; a single story is dangerous as it only shows one perspective and the audience have to form their own perceptions from a narrow point of view. (Tunca, 2009) She goes further to say that most people in the developed world have a single story of Africa.

“My roommate had a single story of Africa: a single story of catastrophe. In this single story there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals. “ (Adichie, 2009)

In the speech she implies that the media is guilty of perpetuating a single story of less developed countries. They might be well meaning but ultimately through the use of terms like ‘tribal’ which depict a backward race they are helping to form stereotypes about Africa.

Ultimately we need to ask ourselves what part the media plays in forming our ideas and stereotypes about wellbeing in LEDCs. Are we guilty of fostering our perceived notions about wellbeing and wealth on a different culture? In the UK, to marry a woman a man might have to produce an engagement ring and the bigger the stone, the better according to conventions. This society puts value on precious stones, jewellery, houses’ the ultimate holiday to the Bahamas etc. It is a product of the country’s history and geography. In the UK water is seen as a common commodity as we have rivers of it. In parts of sub-Saharan Africa, to marry a woman you need to provide the family with a certain number of livestock, tubers etc. In countries like that holidays, diamonds, big houses with the latest gadgets and fashionable clothes are not valued as they are not of top priority. This is not because some cannot afford it. But it is because by its very nature a society values what it does not have an abundance of. For example in the UK precious stones and gold are status symbols because they have to be imported making them expensive. In Somalia land is not valuable but water is, if a rural living Somali man was given diamonds it would be more worthless than water, it does not feed his prized cattle or make the rains fall. We cannot judge a country’s level of wellbeing by comparing what they have with what we have, as cultures are the product of environment.

“In developed economies virtually every activity has been commercialised…national accounts of any western nation include payments for personal beauty care, which for the US is around $60 billion a year. Such an item would hardly feature in the accounts of African nations. However, this does not mean that African men and women living in villages do not enjoy ‘beauty’ treatments – activities are not commercialised. In 1996 Britain spent some $33 billion on beer, wine and spirits…the consumption of palm wine, local spirits and other indigenous alcoholic brews in African villages is not incorporated in national accounts…in capitalist societies, virtually all aspects of culture is monetized and incorporated in the national accounts…total annual expenditure on marriages and funerals in the US runs into several billions of dollars a year…people marry in African societies in elaborate and joyful ceremonies and the dead are buried with appropriate ritual, little of these activities get into the national accounts… Leisure and entertainment sectors account for a large proportion of the GDP of western nations, but in the GDP of poor countries these universal components of life hardly figure…When considering the material conditions of people in Africa, a distinction should be made between absolute poverty and relative poverty…” (Obadina, 2008)

There is no denying the levels of absolute poverty in Africa but is the media guilty of perpetuating a single story to us in the information they choose to show. Are we guilty of succumbing to the single story? Maybe we should ask ourselves, how many times we have seen pictures of Africans living in poverty and assumed the continent is a single story of catastrophe. Although well-meaning, how many of us have fallen into the trap of the single-story portrayed by the media and changed our default position to one of pity? In this are we guilty of robbing a continent of its dignity? Our generation and the generations before got it wrong, however we can still try to rewrite history. By re-educating the new generation of children and teaching them the dangers of single stories, it might be too late for our generation but we have the opportunity to mould the future of our children. As countries become more diverse we need to teach our children the dangers of a single story so they do not get left behind in the ever evolving politics of the dynamic modern world we live in.